Foreign Tunisia Experts vs Local Voices: Determinism or Another Crisis of Liberal Democracy?

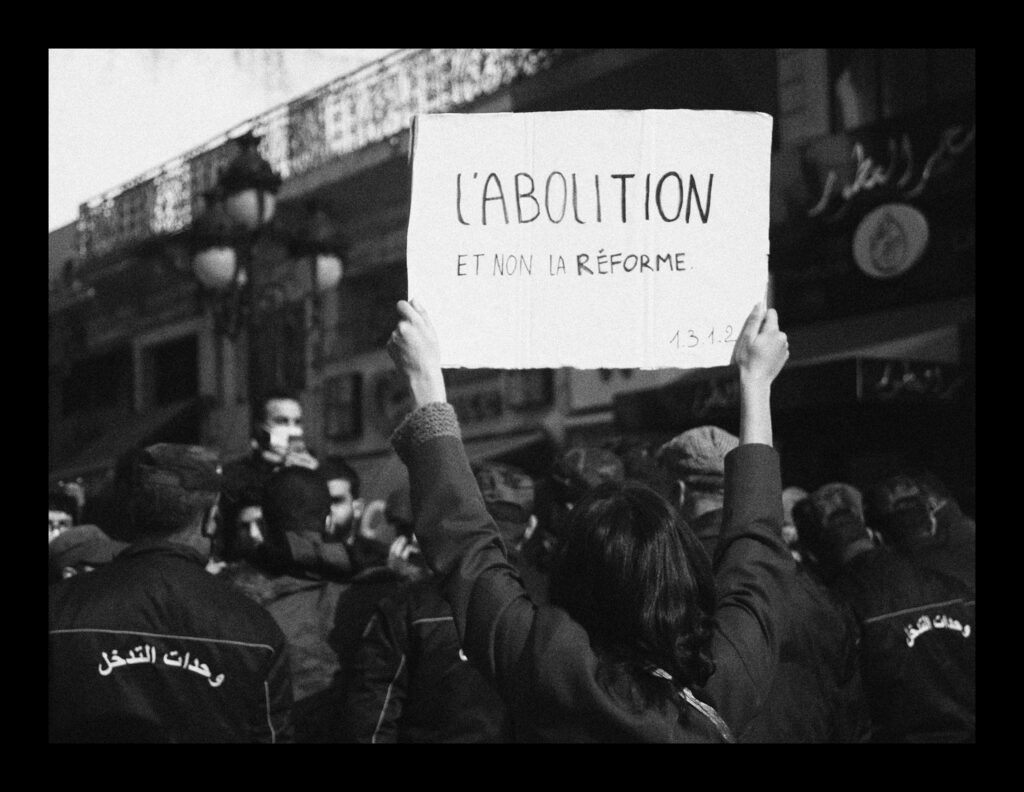

Photo Credit: Emna Fetni

Written by Aymen Bessalah

More two weeks have passed since President Said invoked Article 80 of the Constitution, suspended Parliament, and sacked the Head of Government on July 25,2021. Since then, MENA and Tunisia experts and commentators from around the globe have rushed to proclaim this as a “coup” all while prophesying worst-case scenarios, before qualifications of autogolpe and more recently constitutional dictatorship were presented. In the meantime, Tunisians continue to follow the unfolding situation, with heterogeneous views ranging from considering the situation a “coup”, a transitional period with some or little constitutional grounding, to considering it fully constitutional and necessary to put the revolutionary process (or the democratic transition) back on track. Most scholars and commentators, as well as Tunisian CSOs, consider that the President’s decision to suspend Parliament reflects an abusive reading of Article 80, even if Said considers the Parliament to be a contributing element to the imminent threat according to some statements. Moving beyond the qualifications debate, for lack of space and the abundance of arguments for several positions, this article suggests to view Said’s move from the lens of the crisis of liberal democracy.

On July 25th, 2021, Tunisia witnessed large demonstrations in various regions protesting the decaying socio-economic conditions and the ongoing collapse of the healthcare system. Angry Tunisians in the capital headed towards the Assembly of People’s Representatives (Parliament), while protesters in other regions rallied in front of governors’ offices before attacking and burning local offices of Ennahdha Party in several cities (1). This is but the latest episode of continuing protests as Tunisians are growing more dissatisfied with and disillusioned by ruling elites’ inability to achieve the prosperity that was at the core of their demands in 2011. The long hailed consensus-based politics, while undoubtedly necessary on various junctions, was restricted to elite-consensus that did not produce the socio-economic development nor enact the necessary reforms that Tunisians sought. Ennahdha is the single biggest constant in Tunisia’s post-2011 political landscape, and being a member of all ruling coalitions, many – or some – Tunisians hold Ennahdha as the primary actor politically responsible for the ordeals of the last decade. Furthemore, protests demanded Parliament as a whole to be dissolved as the scenes of physical and verbal aggression and several instances of hate speech became a recurrent theme.

A few hours later, President of the Republic Kais Said caused a political earthquake by invoking Article 80 of the Constitution. The article in question enables the President to take any necessary measures “in the event of imminent danger threatening the Nation’s institutions or the security or independence of the country, and hampering the normal functioning of the State.” Yet, many debate whether the President respected all necessary conditions to invoke the article. Beyond the constitutionality of these measures, they de facto open up various possibilities on the way forward (or backwards) as to the nature of the political system, and even the composition of the political arena. Said’s decision came as a surprise but not as a shock to many, as he has been continuously threatening to use his “constitutional rockets” to fix the ongoing political stalemate. As a matter of fact, a series of political differences and competition over jurisdictions has led to conflicts between the two heads of the executive, the President and HoG, as well as between the President and Speaker of Parliament, ongoing for over a year.

A pivotal and informative point that is still lacking in most analyses presented thus far is Said’s anti- party politics stance as well as the fact that he is an “anti-system” political outsider. Said, a lecturer in Constitutional Law, ran for elections calling for a change towards a presidential system with the legislative springing from regional assemblies, with the latter being a product of directly elected local assemblies. He also believes that voters should be able to revoke any deputy’s membership at any point during their mandate. Moreover, Said has been largely supported due to his “clean” and outstanding background, opposed to the widespread corruption within the political elites that have numerous ties to business elites. Finally, Said has explicitly declared on numerous occasions that the time of party politics is over. This was a focal point of his campaign during which he stated that he had no program, and that it is the people that have programs, and the people know what they want.

Instead of attempting to read Said’s coup de force as a moment of reckoning for liberal democracy in Tunisia, Western commentators opted for deterministic and neo-orientalist readings claiming that Tunisians “maybe never wanted democracy,” with relevant but often misleading comparisons to other experiences in the region. Just as they failed to comprehend the rise of populist right wing anti-establishment parties and leaders all across Europe, and in the USA , they fail to see why Said’s move is an attack against the broken consensus-making process by the ruling elites. What is disturbing is the negationism towards arguments made to point out the current failure and deadlocks the democratic transition in Tunisia suffers from. Another point external commentators miss is that Said believes himself to be a legal and constitutional expert, seizing on loopholes in the constitution and recurrently invoking the issue of legitimacy vs legality. On this specific point, it is important to highlight that not only did Parliament fail to elect its share of members of the Constitutional Court, it has also failed to elect members of 4 out of 5 Constitutional Higher Authorities and to reform authoritarian laws that are enforced but unconstitutional.

Tunisia’s complex and multifaceted crisis can be understood through the prism of state capture, limited statehood, and democratisation theories, but neither lens would solely enable one to fully grasp the state of limbo the country has been trapped in for a decade. Whether or not Said’s power grab would turn into a fully-fledged backsliding towards authoritarianism is yet unknown. Most CSOs are monitoring the situation closely and waiting for Said to announce his roadmap. To many, it is almost undeniable that Said would propose a referendum on changing Tunisia’s political and constitutional order at some point before calling for new elections. Meanwhile, the economy continues to deteriorate and the recent moves by the judiciary are worrying, which has also been ongoing since 2011 as all governments utilised the judiciary to settle scores with political opponents. Local activists continue to be wary of the situation and are hoping for the best. What matters though is that all those who seek to understand the ever-changing dynamics of Tunisia’s politics should try to pay attention to nuances and clarifications, which has sadly become a somewhat challenging endeavour. Such haste to quickly accuse people of coup apologia or fencesitting is troubling, and both locals and foreign commentators could benefit from learning from one another.

(1): Ennahdha Party is considered by many scholars as a moderate Islamist party, especially following their consensus seeking with secularists in Tunisia. Many Tunisians doubt this “Muslim Democrate” narrative and believe they still have ties and loyalties to the Muslim Brotherhood across the region. Ennahdha has ranked first or second in all elections since 2011.